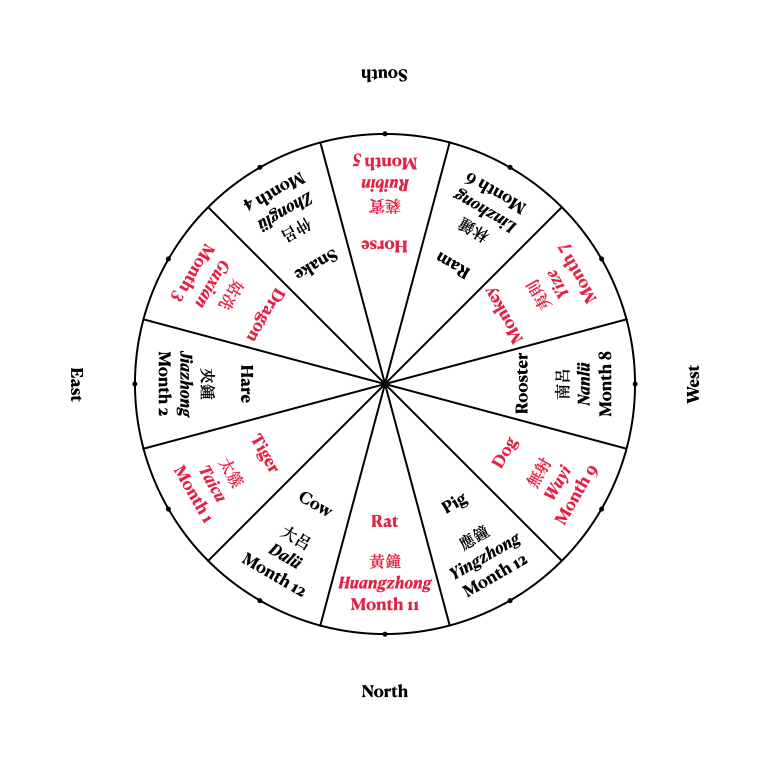

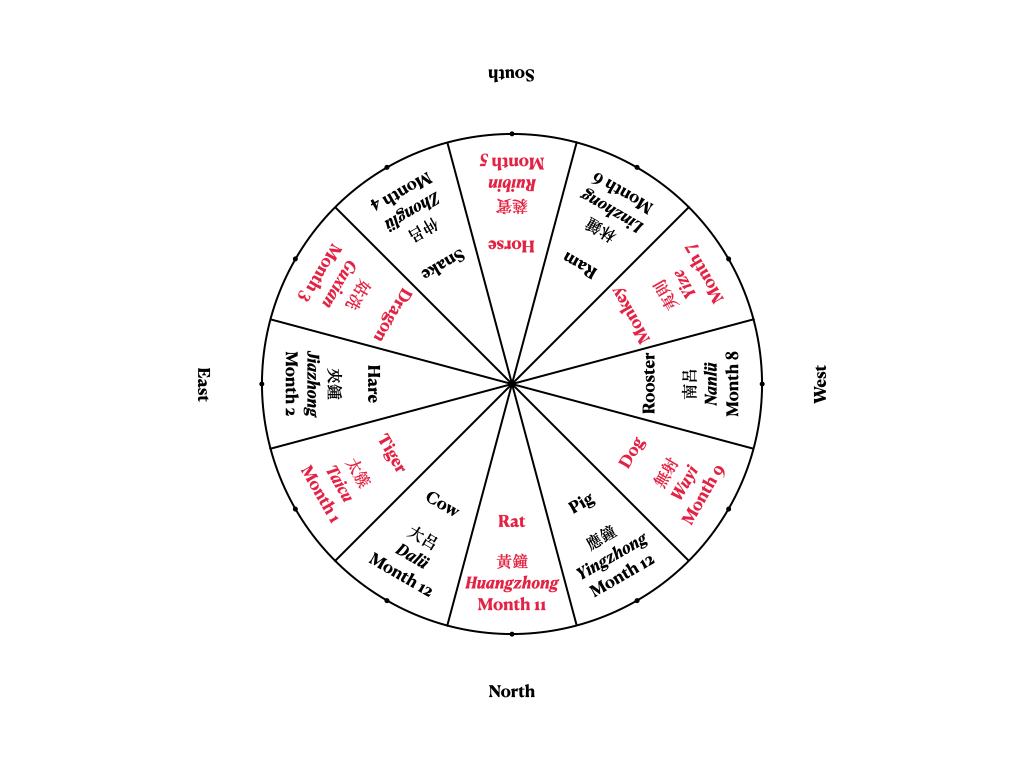

The Twelve Tuning Pitch Pipes and corresponding to the Twelve Earthly Branches (also known as the Twelve Zodiacs), which in turn correspond to the twelve months of the calendar, the four cardinal directions, and the twelve divisions of the night sky. Image made by myself.

This blogpost is part of an ongoing series. For a background introduction of the entire treatise/series, Key Points from the Treatises on Music (c. 680), see the “Translator’s Remarks” of the first post of the series.

Translator’s Remarks

Today I continue my translation of Key Points from the Treatises on Music (c. 680), or “Empress Wu’s Music Theory Primer.” As I have explained in my remarks in the first post of the series, of the three surviving juan of Key Points, juan 5 discusses the seven sheng 聲 (“sounds” and “musical notes”), juan 6 the twelve tuning pitch pipes, and juan 7 the two concepts in combination. Here below are translated Chapters 5:2 and 5:3, which introduce the seven sheng (sometimes also referred to as the seven yin 音 ) or the seven notes of the heptatonic scale, which are gong 宮, shang 商, jue 角, bianzhi 變徵, zhi 徵, yu 羽, and biangong 變宮 in the order of their relative heights.

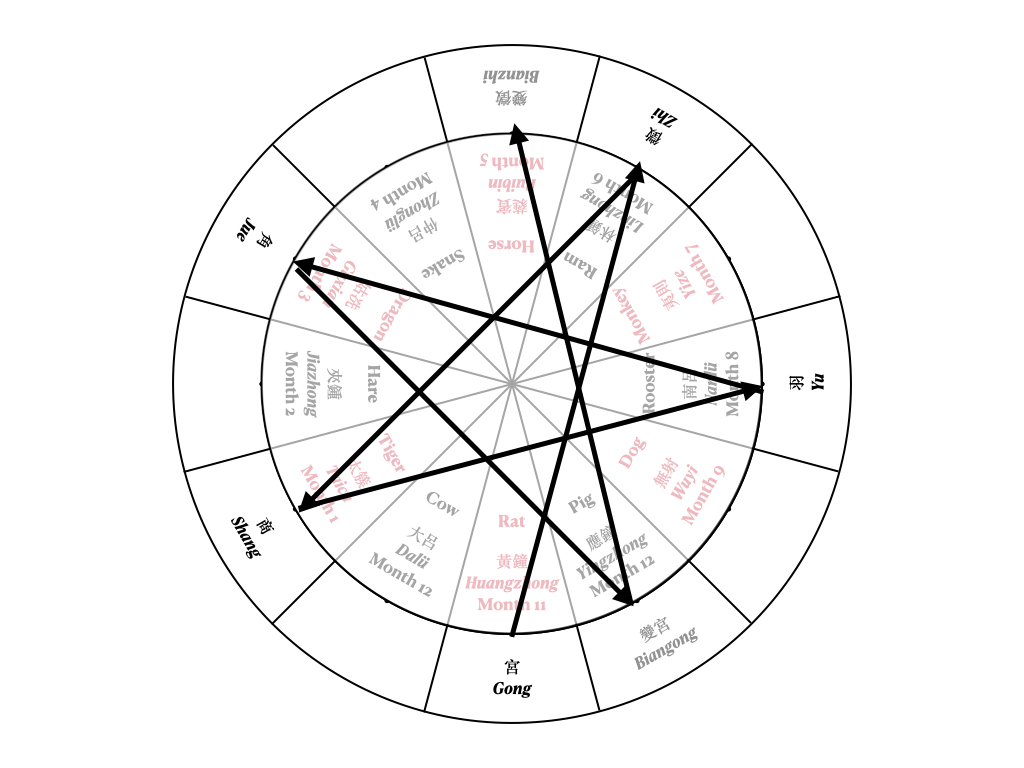

Chapter 5:2 discusses the “mutual generations” of the seven sheng. Mutual generations xiangsheng 相生 refer to the topology of the seven notes of the scale vis-à-vis the twelve tuning pitch pipes. Given the importance of topology, I have made several diagrams in this post illustrating how the seven sheng relate to one another. As you will see, the number “eight” is of particular importance here: many Chinese texts describe the topology between the seven sheng as liba 歷八 “passing by eight ones” or geba 隔八 “at every eighth one” or “eight ones apart.” These descriptions can be rather perplexing (especially if you end up confusing the “eight” here with “octave,” as did the Kangxi Emperor in 1692, as a result of his studying European music theory). But if you closely follow the diagrams, especially the GIF animation, you should see why what is typically described as a “fifth” relationship in European music theory is described as “passing by eight ones” or “at every eighth one” in Classical Chinese texts. Understanding this topology of “eighths” is very important for mastering Chines tuning theory and pitch theory: the same topology is applied to the twelve tuning pitch pipes as well, as a later chapter explains.

Chapter 5:3 discusses two of the seven sheng whose peculiar names may suggest an inferior status vis-à-vis the other five: biangong and bianzhi. The name of these two notes literally mean “the altered gong note” and “the altered zhi note,” which suggest as if they were not proper notes on their own but merely the bian 變 or “altered”—even “deviant”—versions of the original gong and zhi notes. What is more, the seven sheng are often referred in Classical Chinese prose as wusheng erbian 五聲二變, literally “the five notes and the two altered notes,” or wu zhengsheng er biansheng 五正聲二變聲, literally “the five proper notes and the two altered notes.” Such nomenclature apparently divides the seven sheng into two hierarchical classes: (1) the five core notes of gong, shang, jue, zhi, and yu, which effectively constitute a pentatonic scale, and (2) the two auxiliary notes of biangong and bianzhi, which fall outside the “Chinese pentatonicism” stereotype.

As you will see, the authors of Key Points would have adamantly rejected “Chinese pentatonicism” as nonsense. For them, there is practically little distinction between the five pentatonic “proper” notes and the two bian notes. They go as far as saying that no music or melody is possible if one only uses the five “proper” notes without the two bian notes—indicating, perhaps, that a pentatonic melody would have sounded strange or even exotic to their ears. But here, it is important to treat Chapter 5:3 as prescriptivist. In fact, many texts in the Classical Chinese corpus argue, on the contrary, that the two bian notes are in fact qualitatively and theoretically distinct from the five “proper” notes: some assert that they should not be used in certain in formal, solemn occasions at all; some argue that they can be used, except not as the final of any melodic mode; some speculate that they were more recent additions to the more ancient five “proper” notes, and so on. And we haven’t even begun to talk about actual musical practices beyond these prescriptivist debates! Hence keep in mind that, although Key Points and indeed many thinkers from around that time (the Sui and early Tang periods, 6th to 8th centuries CE) believed strongly in the “equity” among all the seven notes, the question of “Chinese pentatonicism” eschews simple answers even in text-based music theory.

Chapter 5:2 “The method for the mutual generation of the seven sheng.”

The gong note generates the zhi note. The zhi note generates the shang note. The shang note generates the yu note. The yu note generates the jue note. The jue note generates the biangong note. The biangong note generates the bianzhi note.

Anyone who wants to comprehend the mutual generations of the seven sheng should do the following. First, arrange the twelve tuning pitch pipes in a circle according to each of their proper positions aligned with the Twelve Earthly Branches See Translator’s Diagram 5:2-1 below. “Twelve Earthly Branches” (dizhi) 地支 refer to a counting system based on. This counting cycle correlates to a variety of twelve-based entities: the twelve months of the year, the twelve shi (時) of the day, the twelve divisions of the sky (shier ci 十二次, a.k.a. fence 分野), the twelve cardinal directions, and, indeed, the twelve tuning pitch pipes. But the most famous correlation is certainly that of the twelve zodiacs—i.e., rat, cow, tiger, hare, dragon, snake, horse, ram, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig. Hence, because the Huangzhong pipe corresponds to the “Rat” Earthly Branch (zi 子), which in turn corresponds to the North, the Huangzhong pipe is accordingly placed in the northern direction; because the Ruibin pipe corresponds to the “Horse” Earthly Branch (wu 午), which in turn corresponds to the South, the Ruibin pipe is accordingly placed in the southern direction; and so on .

Then, choose only one of the twelve pipes as the starting point, and this pipe will be the gong note. Count this gong-note pipe as the first pipe, and Rotate to the left i.e. clockwise to the eighth pipe, which will be the zhi note.

From this zhi-note pipe now counted as the first pipe, count clockwise again to the eighth pipe, which will be the shang note.

From this shang-note pipe now counted as the first pipe, count clockwise to the eighth pipe, which will be the yu note.

From this yu-note pipe now counted as the first pipe, count clockwise to the eighth pipe, which will be the jue note.

From this jue-note pipe now counted as the first pipe, count clockwise to the eighth pipe, which will be the biangong note.

From this biangong-note pipe now counted as the first pipe, count clockwise to the eighth pipe, which will be the bianzhi note.

This method above matches the method for the mutual generations of the tuning pitch pipes as well How these “mutual generations” pan out similarly among the twelve tuning pitch pipes is explained in a later chapter of the treatise.

(For example See Translator’s Diagram 5:2-2 below, for an animated illustration of this example, followed by Translator’s Diagram 5:2-3, let us suppose that the Huangzhong pipe corresponding to the 11th Month is the gong note. Counting from hence to the eighth position, it generates the Linzhong pipe corresponding to the 6th Month, and this Linzhong pipe is the zhi note. Counting from hence again to the eighth position, it generates the Taicu pipe corresponding to the 1st Month, and this Taicu pipe is the shang note. Counting from hence again to the eighth position, it generates the Nanlü pipe corresponding to the 8th Month, and this Nanlü pipe is the yu note. Counting from hence again to the eighth position, it generates the Guxian pipe corresponding to the 3rd Month, and this Guxian pipe is the jue note. Counting from hence again to the eighth position, it generates the Yingzhong pipe corresponding to the 10th Month, and this Yingzhong pipe is the biangong note. Counting from hence again to the eighth position, it generates the Ruibin pipe corresponding to the 5th Month, and this Ruibin pipe is the bianzhi note.

Even though the twelve tuning pitch pipes take turn in being the gong note, the repeating cycles of the seven sheng are all like the method explained above.

Chapter 5:3 “On how to understand the two bian notes.”

The seven sheng were portended by the Primordial Chaos mingmei 冥昧, one of the various terms referring to the original state of the cosmos before creation, i.e. its division into various entities (differentiation of Heaven from Earth, etc.) and engendered by the Self-So ziran 自然; in contemporary Mandarin, ziran is typically translated as “nature” or “natural”; but the term literally means “to be so by itself” or “it is what it is by the virtue of itself.” I typically translate ziran as “self-so,” since the phrase was a very important philosophical term in Classical Chinese, and it does not have the “naturalism” associations that “nature” connotes in modern English . Principle is generated by Heaven, not manufactured by human. Whenever affections and feelings fill up on one’s inside and express outward through singing and chanting, there will be the seven sheng, with which the melodic modes are formed. The Five Proper Sheng wu zhengsheng 五正聲, i.e., the gong, shang, jue, zhi, and yu notes and the Two Bian Sheng i.e. the biangong (literally, “altered gong“) and bianzhi (literally, “altered zhi“) notes complement each another like warps and wefts of a loom, and no tune or melody can form without using the two bian sheng i.e. no tune or melody is possible without biangong or bianzhi being used, in addition to the other five pentatonic notes (gong, shang, jue, zhi, yu) . Hence we know that the two bian notes are the embellishments of the gong note and the zhi note respectively i.e. biangong embellishes gong, and bianzhi embellishes zhi : they are like salt and plum yanmei 鹽梅 “salt and plum” were the primary condiments in Chinese cooking before the popularization of soy sauce and vinegar for the five other notes. The bian sheng assist and facilitate the five other notes, just like gradient paints set off and elaborate the Five Primary Colors wuse 五色, referring to cyan, yellow, red, white, and black .

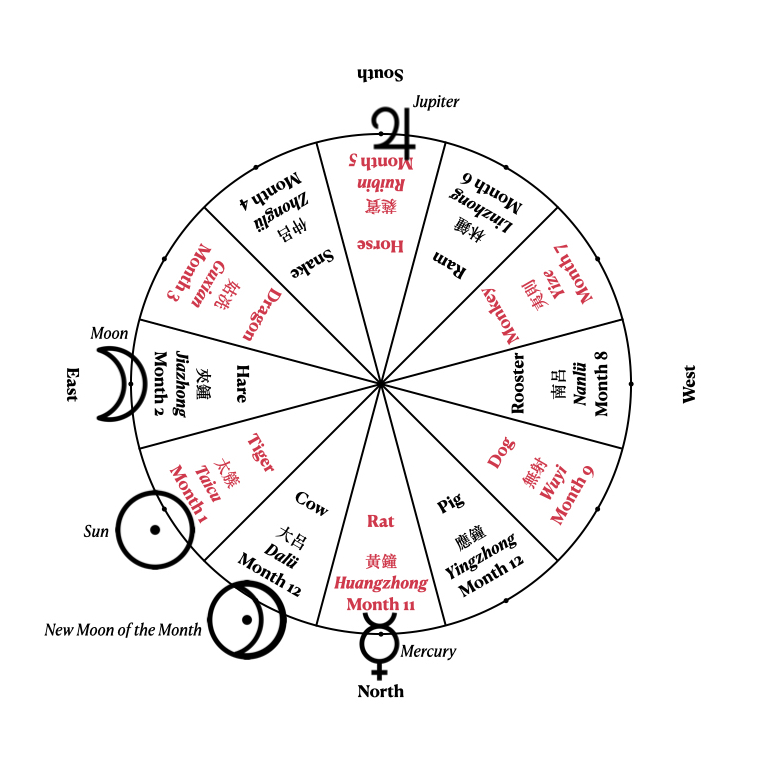

Those who do not understand music do not know the origins of the bian notes. Some once said: “When King Wu of the Zhou 周武王 (c. 1076-1043) or King Wu was the founder of the (Western) Zhou dynasty (c. 1046-771 BCE), the last of the “Three Ancient Dynasties” that was particularly revered by Confucian scholars for the supposed propriety of its rites, music, and institutions vanquished the Shang Dynasty c. 1600-1046; the Shang was the second one of the “Three Ancient Dynasties,” overthrown by King Wu of the Zhou in 1046 , the celestial bodies encompassed seven out of the Twelve Zodiacal Divisions, from Horse to Rat, and he therefore increased the number of musical notes from five up to seven.” See Translator’s Diagram 5:3-1 below; this theory of the origins of the seven sheng—specifically, the expansion of the original five sheng to seven—refers to a star chart in Discourses of the States (國語, c. 4th century BCE), recording the positions of various celestial bodies vis-à-vis the Twelve Divisions of the Sky (shier ci 十二次 or fenye 分野), divisions that in turn correspond to the Twelve Earthly Branches, the twelve zodiacs, the four cardinal directions, and, importantly, the twelve tuning pitch pipes. Essentially, the record suggests that, when King Wu of the Zhou overthrew the Shang Dynasty in c. 1046 BCE, Jupiter was located in the Horse division of the sky (chunhuo 鶉火) in the South, the Moon was located in the Hare division (tiansi 天駟) in the East, the Sun was located in the Tiger division (ximu 析木), the New Moon of that particular month was located in the Cow division (doubing 斗柄), and Mercury was located in the Rat division (tianyuan 天黿) in the North. As shown in Translator’s Diagram 5:3-1 below, these five celestial bodies encompass seven divisions of the sky in total, if one begins with the Horse division and rotate counterclockwise up to the Rat division. Hence supporters of this theory suggest that, because of this horoscopic line up coinciding with his conquest of the Shang, King Wu of the Zhou decided that the five sheng or musical notes must be expanded to seven.

Henceforth, Confucian scholars have been passing down this theory, saying: “the bianzhi and the biangong notes originated as late as under King Wu of the Zhou.” Yet, if this theory were true, the music from the Xia dynasty ? c. 2070-1600 BCE and the Shang dynasty i.e., the first and second of the “Three Ancient Dynasties” predating King Wu and the Zhou dynasty and even earlier times could not have formed any melody—so how was Xiaoshao 簫韶, literally “Harmonious are the Pipes,” a piece of music traditionally attributed to the legendary ancient Emperor Shun (r. ? 2255-2184 BCE) and Daxia 大夏, literally “The Great Xia,” a piece of music traditionally attributed to Yu the Great (r. ? 2123-2025 BCE), founder of the Xia dynasty able to achieve their renowned harmony? This is a theory from those sticklers to written texts and adherents to preconceived opinions, not one from those who actually understand and master music.

This work by Zhuqing (Lester) S. Hu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Original Chinese source in Public Domain: 樂書要錄·卷五.

One thought on “What Pentatonicism? – Key Points from the Treatises on Music (c. 680), Chapter 5:2 “The method for the mutual generation of the seven sheng” and 5:3 “On how to understand the two bian notes””