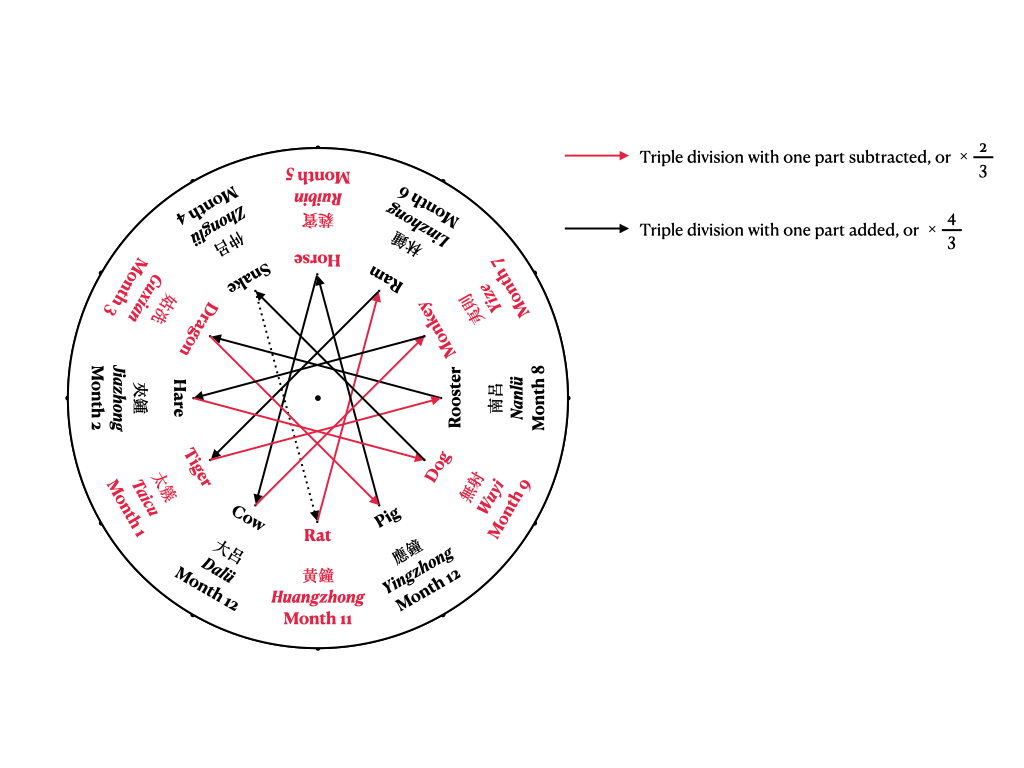

The Twelve Tuning Pitch Pipes with their lengths being generated through compounding multiplications of “triple division with one part subtracted” (=2/3) and “triple division with one part added (=4/3). Image made by myself.

This blogpost is part of an ongoing series. For a background introduction of the entire treatise/series, Key Points from the Treatises on Music (c. 680), see the “Translator’s Remarks” of the first post of the series.

Translator’s Remarks

Onto the third installment of Key Points from the Treatises on Music (c. 680), a.k.a. “Empress Wu’s Music Theory Primer,” the two chapters, translated here, 5:4 and 5:5 continue to discuss sheng or the seven notes of the scale—nominally. To recap, Chapters 5:2 and 5:3 translated in the previous installment not only introduces the seven sheng and insists there be no less than seven (ergo my tongue-in-cheek title, “What Pentatonicism”), but it also introduces an important concept: the “mutual generations” whereby the seven sheng successively generate one another i.e. gong generates zhi, zhi generates shang, shang generates yu, yu generates jue, jue generates biangong, and biangong generates bianzhi. The patterns of these “mutual generations” are also described, in relation to the twelve tuning pitch pipes, as “mutual generation at every eighth step” liba xiangsheng 歷八相生 or geba xiangsheng 隔八相生. But as you can see from Translator’s Diagram 5:4–1 below (a repeat of Translator’s Diagram 5:3–2 from the previous installment), this “mutual generation at every eighth step” among the seven sheng only makes sense in specific relation to the twelve tuning pitch pipes. For example, in the diagram below, gong on Huangzhong generates zhi on Linzhong, and there are “eight steps” total from gong–Huangzhong to zhi–Linzhong only because one counts not the number of notes encompassed on the outer circle but the umber of pitch pipes encompassed in the inner circle i.e., in the clockwise direction, there are Huangzhong (gong), Dalü, Taicu, Jiazhong, Guxian, Zhonglü, Ruibin, and Linzhong (zhi), a total of eight pipes or “eight steps”. In other words, the twelve tuning pitch pipes and their mutual relationships are an inevitable topic, in order to understand the seven sheng and the heptatonic scale.

Therefore, even though, as I have explained in my “Translator’s Remarks” in the installment post of the series, juan 5 of Key Points focuses largely on sheng (the notes and the scale system) while a proper discussion of the twelve tuning pitch pipes will not appear until juan 6, Chapters 5:4 and 5:5 translated below “preview” the twelve tuning pitch pipes by necessity, in order to continue to unravel the “mutual generations” between the seven sheng—which, as we willl are, are really the “mutual generations” between the twelve tuning pitch pipes through successively compounding proportions of 2/3 and 4/3. Collectively, these “mutual generations” between the twelve tuning pitch pipes are known as sanfen sunyi 三分損益 “triple division with one pat subtracted or added”—a neat way, in my opinion, of describing 2/3 “triple division with one part subtracted” and 4/3 “triple division with one part added”. While the treatise both here and later in juan 6 stays rather close to this rather canonical method of “generating” the lengths of the twelve tuning pitch pipes, it does claim to bring an element of novelty. As we will see, this novelty resides in its pronouncement that—unlike many scholars both earlier and later who made a huge fuss about when and where you should apply 2/3 as opposed to 4/3 (and vice versa) and conjured various cosmological justifications therefore—ultimately, it does not matter whether, when, or where one applies 2/3 or 4/3. Instead, the core of the method is “triple division,” not the second half of the phrase.

On the paradigm of mutual generations

Of all mutually generating sheng, the paradigms are no different Such “mutual generation” between the seven sheng in relation to the twelve tuning pitch pipes is explained in the previous two chapters; see Translator’s Diagram 5:4–1 above, again, for a review of the “mutual generations”. Each pair of mutually generating sheng are distinguished into a higher one and a lower one. When listening to them for the first time, one may become confused. And yet, if one discerns their relation with respect to the clear vs. the muddy i.e. with respect to which ones are higher and which ones are lower; qing 清 “clear,” “translucent” is often used to describe higher sounds, whereas its antonym zhuo 濁 “muddy,” “turbid” is often used to describe lower sounds , then all such relations of mutual generations between two sheng turn out to be equivalent and repetitive.

(Whenever one suspects that a muddy sheng deviates from the paradigm, examine it in reference to its corresponding clear sheng in a pair of “mutual generation”; for example, if the shang note sounds out of tune, examine it in reference to the zhi note, which (1) generates the shang note in the “mutual generations” of the seven sheng (see Translator’s Diagram 5:4–1 again for a review), and (2) is “clearer” than the shang note it generates . Whenever one suspects that a clear sheng deviates from the paradigm, examine it in reference to its corresponding muddy sheng in a pair of “mutual generation”; for example, if the zhi note sounds out of tune, examine it in reference to the gong note, which (1) generates the zhi note in the “mutual generations of the seven sheng, and (2) is “muddier” than the zhi note it generates; cf. Translator’s Diagram 5:4–1 again. When one finds that the clear and the muddy in any pair of mutually generating sheng are of the same sheng everywhere i.e. every pair of mutually generation clear and muddy sheng are separated by the same interval between them; “the same sheng” here can only be understood as “interval,” in order to make sense, then one knows that the mutual generations between all sheng follow the same paradigm i.e., if the gong–zhi, zhi–shang, shang–yu, yu–jue, jue–biangong, and biangong–bianzhi intervals all sound the same (“are of the same sheng“), one knows that all these pairs of notes following the same paradigm of “mutual generation” . Therefore, we know that, when gong generates toward zhi, when zhi generates toward shang, when shang generates toward yu, when yu generates toward jue, when jue generates toward biangong, or when biangong generates toward bianzhi, the same paradigm is followed without any exception—and we understand this by means of examining the clear and the muddy sheng.)

Whenever a sheng is halved or doubled, Here the authors are likely speaking not (only?) in terms of any abstract or numerological “harmonic numbers”, but in terms of concrete lengths—i.e., the lengths of strings or the lengths of pipes. Indeed, the “category mistake” between sounds (sheng) and their producers (e.g. a pipe or a string) is commonplace in this text and in Classical Chinese prose at large. Where standard European nomenclature would say “one octave lower” or “one octave higher,” the rough equivalent terms in Classical Chinese were “half sheng” (半聲) and “double sheng” (倍聲)—”octave” was not even a verbalized concept in Classical Chinese theory! it still remains the same sheng except being clearer or muddier. All hearing persons can perceive this without having to wait for someone knowledgeable in music to point it out. If one wants to understand this through numbers, one need only the “reverse method” of the “subtractions and additions up high and down below” Here, “subtractions and additions up high and down below” (損益上下) refer to sanfen sunyi 三分損益 “triple divisions with one part subtracted or added.” This was the canonic method for calculating the lengths and proportions of the twelve tuning pitch pipes, first written down in the 3rd century BCE. In this method, one begins with a prescribed length of the Huangzhong pipe and computes the lengths of the remaining eleven tuning pitch pipes by successively multiplying this length by “triple division with one part subtracted” (=2/3) and “triple division with one part added” (=4/3); see Translator’s Diagrams 5:4–2 and 5:4–3. But the author of this treatise argues for a method that “reverses” the normative “triple division with one part subtracted or added.” How they “reverse” the latter is explained in their parenthetical remarks in the next paragraph. If one only divide with “triple division” without subtracting or adding one part, one will obtain the sheng in halves i.e., if normatively one should multiply the length of a pipe or a string by 2/3 (“triple division with one part subtracted”) or 4/3 (“triple division with one part added”), and one only multiplies it by 1/3 (“triple division”), then the resulting pipe or string will only be 1/2 or 1/4 of the pipe or string that corresponds to the proper sheng.

(Suppose that the Huangzhong pipe is 9 cun a cun (寸) is a unit of length; while its standard varied, it was typically in the same order of magnitude as an inch, and the Linzhong pipe is 6 cun according to “triple division with one part subtracted”: 9 times 2/3 equals 6. In the old method, one would “triple divide” the Huangzhong pipe “with one part subtracted” and generate a shorter Linzhong pipe down below xiasheng (下生) “generating down below” refers to when a longer pipe generates a shorter pipe: when two pipes are erected vertically one their base, the shorter one is naturally “down below” the longer one. But now, let us generate a double-length Linzhong pipe, which is 1 chi 2 cun a chi (尺) is a unit of length one order of magnitude larger than cun; here, 1 chi = 10 cun; for this we must “triple divide the Huangzhong pipe with one part added” i.e. multiply the Huangzhong pipe’s length by 4/3 and only then can we get a longer Linzhong pipe up above the Huangzhong pipe shangsheng (上生) “generating up above” refers to when a shorter pipe generates a longer pipe: when two pipes are erected vertically on their base, the longer one is naturally “up above” the shorter one. The old method stipulated a generation down below = generating a shorter pipe, whereas the current method a generation up above = generating a longer pipe. The old method stipulated a “triple division with one part subtracted” i.e., 9-cun Huangzhong times 2/3 equals 6-cun Linzhong, whereas the current method a “triple division with one part added” i.e., 9-cun Huangzhong times 4/3 equals 1-chi-2-cun Linzhong. This is why the current method is called the “reverse method of subtractions and additions up high and down below” since where the convention stipulates a 2/3 “down below” generation, this new method proposed here uses instead a 4/3 “up above” generation. When it comes to the Linzhong pipe generating the Taicu pipe, the old method stipulates a “triple division with one part added” generating a longer pipe up above: this is because the Taicu pipe is 8 cun and the Linzhong pipe is 6 cun, in terms of lengths i.e., 6-cun Linzhong times 4/3 equals 8-cun Taicu. But if the aforementioned 1 chi 2 cun–long Linzhong pipe is to be used instead, a “triple division with one part subtracted” must also be used instead i.e., 1-chi-2-cun Linzhong times 2/3 equals 8-cun Taicu, even though the “triple division” proportions are no different from the previous ones i.e., the proportion is always either 2/3 or 4/3, regardless of the order whereby they are applied. What is more, if one halves the Huangzhong pipe and Taicu pipe into 4.5 cun and 4 cun, respectively, yet keeps the Linzhong pipe at 6 cun unchanged, here again, the halved Huangzhong pipe can still generate a longer Linzhong pipe up above through “triple division with one part added”: 4.5-cun Huangzhong times 4/3 equals 6-cun Linzhong, and this latter Linzhong pipe can still generate a shorter Taicu pipe now also halved still down below through “triple division with one part subtracted”: 6-cun Linzhong times 2/3 equals 4.5-cun Taicu. If these procedures are to be used as the standard, all the rest can be similarly derived. In relation to the method of obtaining the “mutually generating” relations between sheng and between pitch pipes by using numbers, this is essential.

On “triple division with one part subtracted or added” being applicable to strings and pipes

No matter how long or short a qin 琴, also referred to as the 古琴 guqin (“the ancient qin“), a plucked-string instrument often translated either as the “Chinese zither” or the “Chinese lute” is, take any one of its strings and adjust it, so that it has the same sheng as the 9-cun-long Huangzhong pipe. On this very string, divide it into three equal-length parts, subtract one part from it, and pluck the remaining two parts, i.e. 2/3 as long as the open string: this will accord to the 6-cun-long Linzhong pipe. Divide this new string segment into three equal-length parts of its own, add one equal-length part to it, and pluck the total four parts, i.e. 4/3 as long as the previous string segment, or 8/9 as long as the open string: this will accord to the 8-cun-long Taicu pipe. Through alternations as such, there will ultimately be twelve finger positions whose sounds are equivalent to the tuning pitch pipes, without even a hao or a li of difference hao and li are units of length three and two orders of magnitude smaller than cun, respectively.

Pipa 琵琶, a class of divergent lute-like, fretted, plucked string instruments of varying shapes, numbers of strings, and purported provenance, extremely popular during the Tang period and extensively intertwined with cultural and musical exchanges between China and Central Asia at the time, chiba 尺八, a type end-blown bamboo flute with finger holes, known as shakuhachi in Japanese; the name literally means “1 chi and 8 (cun)”, and the transverse di 笛, also referred to as dizi 笛子, a type of transverse flute with finger holes also use these as the standard Here, it is argued that the same 2/3 and 4/3 proportions of “triple division with one part subtracted or added” can be applied to the lengths of both strings and pipes; in reality, of course, certain adjustments must be made to applying such proportions to the pipes. While such “end corrections” for pipes were considered by various Chinese music theorists (earlier and later), they are not a concern for this treatise. Hence it can be clearly known as triple division with one part subtracted or added conform with the Primordial Numbers of the cosmos, that it derives its principle from the Self-So ziran 自然, a word often used to mean “nature” in contemporary Mandarin as opposed to any artificial invention.