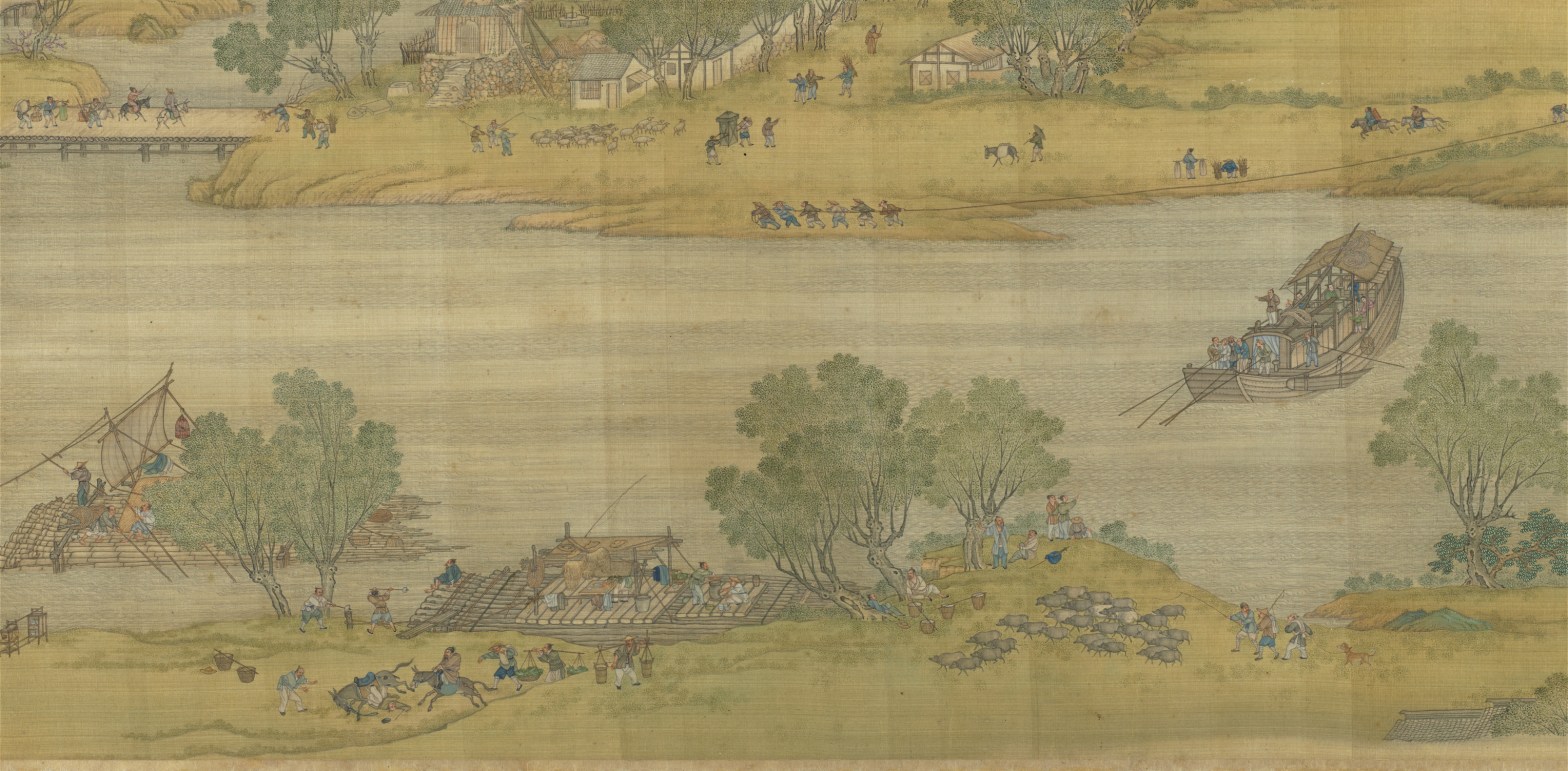

Depiction of River Bian (in Kaifeng) by Qing court painters. Image courtesy of 國立故宮博物院.

Translator’s Remarks

The most important political term in Classical Chinese is mingjun 明君 “enlightened ruler”, which literally means “brightened ruler,” in contrast to the lesser-known anju 暗君 “darkened ruler.” Here, one might be tempted to argue that traditional Chinese political philosophy is “ocularcentric”—except surveying its key texts, figures, and anecdotes suggests that the sense and notion of listening plays just as important a role in the conceptualization of rulership. Arguably, a perfect ruler in the Confucian political imagination is an all-hearing ear. Hence the quasi-synesthetic word jianting ze ming 兼聽則明 “one becomes enlightened this ming “enlightened” is the same ming in mingjun “enlightened ruler” by listening to all perspectives. What is more, not only must the ruler passively receive the sounds, words, and voices from all places and perspectives, but they must also actively seek them out—indeed extract them from across the realm. Hence the long-lasting narrative that the legendary ancient sage kings sent officials into the common folks to listen to their songs, which are used—based on their words and their musical qualities (e.g. the precision of their tuning)—to judge whether the country is on the right track.

The text translated below is the most direct and influential manifesto of this political significance of listening; it is taken from Discourses of the States (國語, c. 4th century BCE), a collection of speeches and conversations between various rulers and their advisors from roughly the 8th to the 5th centuries BCE—hence a key source in traditional Chinese political philosophy. I cannot overemphasize just how much I love this piece of writing here. It plays with the sense of sight and/vs. the sense of hearing in discussing politics. It uses the metaphor of flood to describe the mouths of the people—which both make complete sense given the importance of flood management in the Yellow River plains (or any agricultural zone in the late Bronze/early Iron Age), and suggests interesting parallels with the water, flooding, and dams metaphors in early Romantic writings on sound and the senses (e.g. Johann Gottfried Herder). Most importantly, the moral lesson gives me the chills. As you will see, the Duke of Shao tries to convince the (according to tradition) oppressive King Li of the Western Zhou both lived toward the end of the Western Zhou, in the 9th century that a ruler must open up the people’s mouths and listen to what they say; otherwise, the muffled mouths of the people will one day burst into rebellion, just like a dam without letting any water through will one day be bursted. But doesn’t this present an extremely cynical view—so cynical that it is somewhat realistic—of civil society? Doesn’t this mean that the whole point of free, open public discourse is but a pressure valve sustaining those in power? Doesn’t it make the whole notion of “we need to listen better” look like an extremely cunning ploy?

The Duke of Shao Remonstrating with King Li on Eliminating Criticism

King Li of the Zhou 周厲王 r. 877-827 BCE was oppressive, and the citizens of the capital criticized him. The Duke of Shao 邵公穆, a member of the ruling clan of the Zhou reported to the King and said: “Your people cannot bear your rule!” The King became angry. He summoned a sorcerer from the Wei region to surveil his critics. Those snitched on by the sorcerer were put to death. The citizens did not dare say anything, only gesturing with their eyes when passing each other on the streets Sight substituted for sound! .

The King was pleased. He told the Duke of Shao: “I managed to eliminate criticism, and thus no one dare say anything!” Duke Shao replied: “What you did was only to dam criticism. Damming the mouth of your subjects is more devastating a mistake than damming a river. If a dammed river still ends up bursting the dam, it will necessarily lead to many casualties—and the people are just like that. For that reason, river managers dredge rivers up so as to make them flow without obstruction , and rulers of subjects open the people up in order to make them speak without hindrance . Therefore, when the Son of Heaven listens to the matters of the state, he makes noblemen, ministers, and all the gentlemen present poetry. He makes blind music masters gu 瞽; the word literally refers to those who have eyeballs yet are blind, but it also refers to blind music masters serving the courts of the ancients, apparently a typical practice in the legendary ancient era present songs, chroniclers present histories, teachers present moral lessons. He makes the anophthalmic ones sou 瞍, those without eyeballs chant and the blind ones meng 矇, those who have eyeballs yet are blind recite. He makes all the officials remonstrate and all those without ranks or title submit their reports. He makes his close ministers admonish him to the greatest extent, and he makes his blood-kin and in-law relatives scrutinize his mistakes and make up for them. Blind court musicians and chroniclers teach him and persuade him, and the elders at his court edit such songs and writings, so he may reflect on them carefully. And thus, the affairs of the state can be carried out without errancy.

“The people have mouths, just like the Earth has mountains and rivers where all wealth and wares arise, as well as flatlands, swamps, marshes, and arable fields where all clothing and food grow. The mouths of the people express words, where all the good and the bad of the state’s affairs are manifest. Implementing what is good and guarding against what is bad serve to enrich the wealth, wares, clothing, and food of the state. Indeed, the people think in their hearts and express through their mouths: whenever thinking takes form, its expression takes place. How can this be obstructed in any way? If their mouths were to be obstructed, how long can such obstruction hold up?”

The King did not listen. As a result, the citizens still dared not emit any words —until three years later, when they rebelled and exiled the King to Zhi.

This work by Zhuqing (Lester) S. Hu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Original Chinese source in Public Domain: 國語·卷一·邵公諫厲王弭謗.