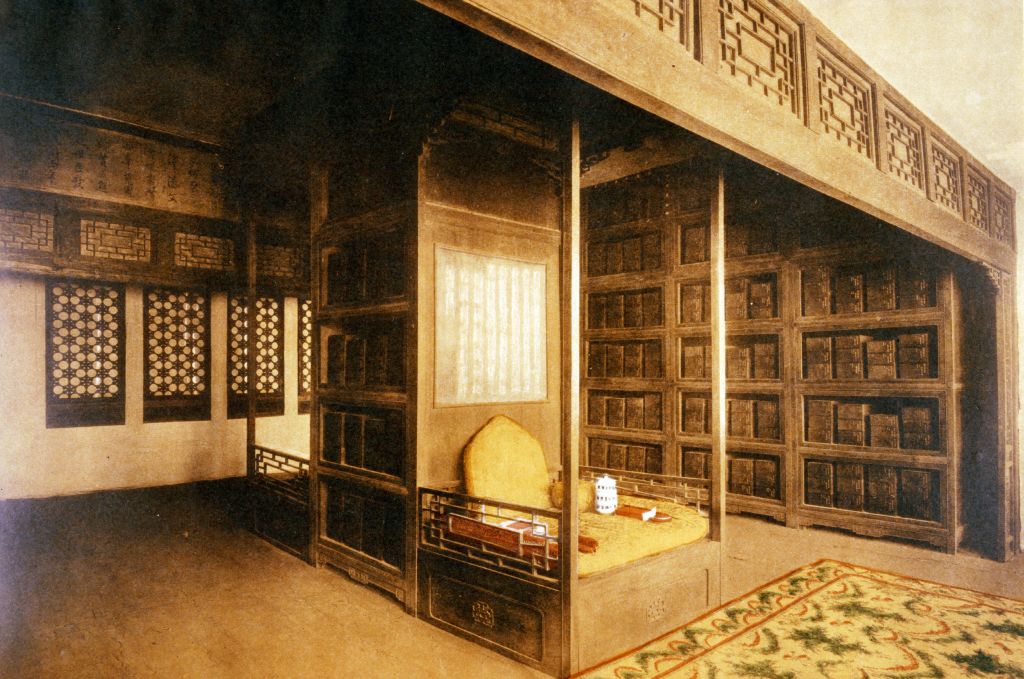

The Complete Library in Four Sections stored at the Forbidden City. image courtesy of 故宫博物院网站

This blogpost is part of an ongoing series.

Translator’s Remarks

What is music? And is “music” a mistranslation for the Chinese concept of yue (樂)? Rather than defining exactly what “music” or yue is, dictionary style, I find it more stimulating to ask where music/yue falls within a particular mapping of the structure knowledge—for which a fancier word would be episteme. While many important cartographies of knowledge existed in the Classical Chinese corpus, arguably the weightiest due to its proximity to imperial power was The Complete Library in Four Sections (四庫全書, 1784/1803), published by the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1796). The largest edited anthology of books in Chinese history, The Complete Library has an accompanying Summary Catalogue and Annotated Bibliography (總目提要). This 200-volume work catalogues more than ten thousand books according to the traditional “four sections” bibliographic classification:

- Confucian Canons (jing 經): editions, annotations, and studies of the core Confucian corpus and philology; 10 categories, including “Music.”

- Histories (shi 史): histories, biographies, administrative manuals, political documents, geographies, and catalogues; 15 categories.

- Arts and Philosophies (zi 子): classics of non-Confucian schools of thought and writings on various arts, trades, and sciences; 14 categories.

- Literary Anthologies (ji 集): anthologies of poetry, essays, and songs and literary criticism; 5 categories, including “Lyrics and Arias.”

Each of these sections (bu 部) comprises several categories (lei 類). Not only is every single book given a summary, but each category also features an introduction, sometimes also a postface. Each introduction and postface explains how compilers of the catalogue understand what books belong to the category at hand and what do not. They therefore offer precious insight into the compilers’ mapping of the structure of knowledge.

Here below are translated the introduction and postface for the “Music” category under the “Confucian Canons” section. In explaining their bibliographic decisions in the introduction, the compilers draw a specific boundary between what constitutes “music” as part of the “Confucian Canons” (the core of the Confucian textual tradition) and what does not. The postface further declares what the core of this “music” should be: music theory, namely tuning theory. It also specifies the exact way to study music theory: not through metaphysical speculations, but through numbers and instruments. This very particular epistemological mapping of music and music theory resonated with various intellectual trends in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Chinese scholarship, particularly the “concrete learning” (shixue 實學) and “evidential learning” (kaozheng xue 考證學) movements that valued empirical and evidentiary methodologies. Lastly, I note that the compilers are particularly fond of using sarcasm when attacking what they considered bibliographic and/or epistemological mistakes of previous scholars.

Introduction to the “Music” Category under the “Confucian Canons” Section

According to Shen Yue 沈約 (441-513) , the Canon of Music was lost under the Qin 221-206 BCE, traditionally the first “unified” dynasty in Chinese historiography. The “loss” here refers to the infamous “Burning of Books and Burying of Scholars,” when the First Emperor (259-210 BCE) persecuted Confucianism along with many other schools of thought, supposedly leading to the loss of many ancient texts. Nonetheless, a survey of ancient books shows that only the chapter “Explicating the Canons” “Jingjie” 經解 in the Book of Rites Liji 禮記 (c. 1st century BCE), one of the three texts that constitute the “Canon of Rites” says: “edify with the Canon of Music.” In his Greater Commentaries on the Canon of History Shangshu dazhuan 尚書大傳 (c. 2nd century BCE), an annotative commentary on the Canon of History (Shangshu 尚書), Fu Sheng 伏生 quotes the words “roaming around the Imperial Academy,” and he claims that this quote comes from a Canon of Music. Yet no other book ever mentions the existence of any Canon of Music. (We note: the “Treatise of Canons and Books” 經籍志 in the Book of the Sui Suishu 隋書 (636/656), the official history of the Sui Dynasty (581-618) compiled by its successor, the Tang Dynasty (618-907) records a Canon of Music in four volumes, and this turns out to have been compiled by Wang Mang 王莽 (45-23 BCE), an usurper during the Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE) made notorious in subsequent historiography, hence everything he compiled became suspect in the third year of the Yuanshi Era 3 CE . And so, whenever Jia Gongyan 賈公彥 (c. 7th century) mentions “The Canon of Music says that …” in the section “chime makers” 磬氏 in the “Records of the Trades” chapter 考工記 in his Commentaries on the Meaning of the Rites of the Zhou Zhouli yishu 周禮義疏 (c. 7th century). The Rites of the Zhou (Zhouli 周禮, c. 2nd century BCE) was one of the three texts constituting the “Canon of Rites,” and it gives an idealized description of rites and rituals under the Western Zhou dynasty (1046-771 BCE), the last “ancient” dynasty in traditional Chinese historiography. Its “Records of the Trades” describes craftsmanship, including organology , he must have been referring to that book compiled by Wang Mang and not to any ancient Canon of Music.) Still, on account of the fact that music spreads happiness and heralds peace, that it moves spirits and humans, that it communicates with Heaven and Earth, and that its usefulness is extremely grand and its meaning extremely subtle, the ancients venerated the edifying power of music and counted it alongside the Confucian Canons even though Canon of Music never existed as an actual text in itself . Therefore, in later periods, books on bells and tuning have been catalogued under the section of “Confucian Canons,” as opposed to the “practical arts” category under the “Arts and Philosophies” section 子部·藝術; this category in The Complete Library includes the following subcategories: calligraphy and painting; qin zither; inscriptions; and miscellaneous arts .

And yet, if we survey the classification of knowledge and books since the Han era 206 BCE-220 CE , we see that books catalogued under heading of “Music” have included both those on the elegant ya 雅 “elegant,” “highbrow,” “courtly,” generally referring to music of the Confucian sacrificial rites and court ceremonies and those on the vulgar su 俗 “common folk,” “popular,” “lowbrow,” generally referring to music associated with the commoners, the illiterate masses, pleasures, and entertainment . Thus, licentious ditties and courtesans’ zither songs have been placed in the same rank alongside the Yunmen 雲門 and the Dashao 大韶; both Yunmen and Dashao were supposedly the music of the ancient sage kings according to Confucian legends and were therefore deemed the epitome of the “elegant”; Yunmen was attributed to the Yellow Emperor (? r. 2698-2598 BCE), Dashao to Emperor Shun (? c. 2294-2184 BCE) . In consequence, in the bibliographies of the Twenty-Four Histories The Twenty-Four Histories were the official dynastic histories endorsed by successive Chinese regimes as the “orthodox history” (zhengshi 正史). Each of these histories records a particular dynasty and/or period. They all follow a specific paradigm, whereby they will feature a dedicated bibliography listing all the important books for the dynasty/period under question , even books on matters as trivial as the zheng zither and the pipa are catalogued at the end of the “Music” category” under the “Confucian Canons” section. If we were to follow this practice, we would note that unapproved histories, anecdotes, and hearsay also record the words of individuals and the courses of events—but does this mean we should be cataloguing these books under the category of “Canon of History” Shangshu 尚書 (c. 2nd century BCE), a collection of edicts and speeches of ancient kings dating back to supposedly as early as the 2nd millennium BCE and “Chronicles of Spring and Autumn” Chunqiu 春秋 (5th century), a chronicle covering the period 772-481 BCE traditionally attributed to Confucius himself under the “Confucian Canons” section as well Both Canon of History and Chronicles of Spring and Autumn were not just Confucian canons but also considered the foundational texts of historiography ? The violation of ethical principles and the harm to moral edification reached such an extreme in such bibliographic practice referring to the “even books on matters as trivial as …” sentence .

Therefore, here unlike before, we distinguish between different kinds of books. Only books that apprehend the tuning pitch pipes lülü 律呂 and elucidate the elegant ya 雅 music are listed, as they have always been, under the “Confucian Canons” section. As for ditties, theatrics, accompanied songs, and lascivious tunes, these are categorically excluded here and relegated instead to the “miscellaneous arts” category under the “Arts and Philosophies” section and the “lyrics and arias” category under the “Literary Anthologies” section . We use this categorization to make clear that the Way of the Grand Music and the Original Yin of the Cosmos Muyin 母音; yin = “tone,” “musical note,” “resonance” resonate with Heaven and Earth, and it shall not be violated by the licentious sounds of the Zheng region The Zheng 鄭 region was infamous for its supposedly licentious songs during Confucius’s time. As such Zhengsheng 鄭聲 “sheng [sound, musical note] of the Zheng region” had long been established as a metonym for morally suspect and lascivious music .

Postface to the “Music” Category

We note: astronomy and musical tuning yuelü 樂律 are both studies based on numbers. Astronomy becomes more and more precise through more and more computations; as a result, previous generations can never rival later generations. In contrast, the longer the time passes, the more the study of musical tuning goes astray; as a result, later generations can never rival previous generations.

Here is the reason. While there are manifest phenomena to measure in astronomy, there is no instrument to rely on in musical tuning. Scholars of the Song era 960-1279; a period known for the rise of the so-called “Learning of the Principle” (lixue 理學), sometimes also referred to as Neo-Confucianism, of which a defining characteristic is its proclivity for metaphysical meditations never procured the proper instruments for musical tuning. They therefore prevaricated by rambling on the principle of music and the origin of music. That music arises from the accord in the human mind and takes its root in the abundance of the ruler’s virtue: this, indeed, is the principle of m music and the essence ben 本, which can also be translated as “origin,” but I think it’s closer to meaning “essence” here, given the lack of any notion of temporality in this particular discussion here of music. Among those who reached perfection with respect to understanding this principle and essence, none ever surpassed Emperor Yao and Emperor Shun. And yet, the music Hou Kui instituted Hou Kui 后虁 was the music master of Emperor Shun, who ordered him to establish what was the earliest institution of court music, according to tradition was still rigidly embedded in the notes, scales, instruments, and numbers shengyin qishu 聲音器數 . Why? Because without nots, scales, instruments, or numbers, there is nothing on which the principle of music or the essence of music can depend. Had the varying lengths of all the twelve tuning pitch pipes lülü 律呂 failed to follow the patterns of Yin and Yang Yin 陰 is sometimes translated as the “feminine” principle, whilst Yang 陽 the “masculine” principle. here it suffices to note that odd numbers are considered Yang and even numbers are considered Yin. By extension, the odd-number pitch pipes (known as lü 律) are also considered Yang, the even-number pitch pipes (known as lü 呂, note different character) are also considered Yin , or the the melodic modes gongdiao 宮調; very roughly, gong can be translated as “transpositions” (akin to “keys”), and diao can be translated as “mutations” (akin to “modes”) of all musical instruments bayin 八音 “The Eight Timbres.” The Eight Timbres (yin = “timbre,” “sound,” “tone”) refer to the traditional Chinese classification of musical instruments according to their materials: metal, stone, wood, leather, silk, earth, bamboo, and gourd. As such it is also a metonym for all musical instruments combined failed to distinguish between the high and the low, not even at the courts of Emperor Yao or Emperor Shun despite their perfect understanding of the principle and essence of music could these pitch pipes and instruments have formed any proper sound sheng 聲 here not only refers to “sound” in general but also connotes “musical sounds” in particular . Therefore, aren’t vague discussions of “the principle of music” and “the essence of music” nothing but bombastic words mounting to nothing?

Therefore, when selecting books to include in this category, we have focused mostly on those that investigate and explain musical tuning lülü 律呂, literally “tuning pitch pipes; because tuning pitch pipes are the go-to instruments for studying tuning in traditional Chinese music theory, they had long become a metonym for musical tuning and music theory at large . This is because we value those that are produced meticulous and are applicable to actual use.

This work by Zhuqing (Lester) S. Hu is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Original Chinese source in Public Domain: 四庫全書總目提要·卷三十八·經部三十八.